At a Glance: The Hustle Stats

| Metric | Details |

| :--- | :--- |

| Visionary | Howard Schultz |

| Original Product | Whole beans only (No cups of coffee) |

| The "Low Point" | 217 investors said "No" to the idea |

| The Risk | Closing 7,100 stores simultaneously in 2008 |

| The Result | 35,000+ Stores & $100B+ Valuation |

Most people think Starbucks was built on roasted beans and caffeine. They are wrong.

Starbucks was built on the memory of a broken man lying on a couch in the Brooklyn projects, staring at the ceiling with a cast on his leg, wondering how he would feed his children.

That man was Fred Schultz. And his son, Howard, would spend the rest of his life trying to build the company his father never had the chance to work for.

This is the story of how a boy from the projects turned personal pain into a $100 billion global sanctuary.

Part 1: The 7-Year-Old Delivery Boy

The year was 1961. Canarsie, Brooklyn.

Howard Schultz was 7 years old coming home from school. As he walked into his family’s small, cramped apartment in the Bayview Housing Projects, he saw his father, Fred, sprawled out on the couch.

Fred was a truck driver. He had been delivering cloth diapers when he slipped on a patch of ice and shattered his ankle and hip.

In 1961, if you were a blue-collar worker and you couldn't work, you didn't get paid. There was no worker’s compensation. No severance. And most importantly—no health insurance.

The family was destitute. Howard remembers answering the door when debt collectors came knocking, lying to them that his parents weren't home while his mother hid in the kitchen.

He watched his father—a proud, hardworking army veteran—wither away. Fred became bitter. He felt discarded by the system. He felt like he had no dignity.

Howard made a silent vow that day, one that would drive him for decades: "If I ever get in a position to lead people, I will never leave them behind."

**

Part 2: The Magic of Milan

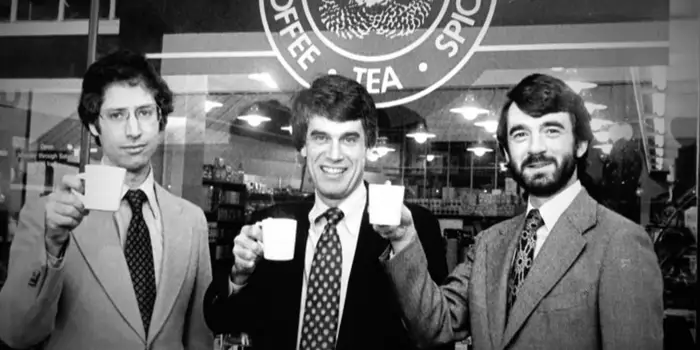

Fast forward to 1983. Howard had clawed his way out of the projects. He was working as a marketing director for a tiny, local coffee bean roaster in Seattle called Starbucks.

At the time, Starbucks didn't sell cups of coffee. They only sold bags of beans.

Howard took a business trip to Milan, Italy. As he walked the streets, he was mesmerized. He saw espresso bars on every corner. But they weren't just selling caffeine—they were selling connection.

The baristas knew the customers' names. People were laughing, talking, and arguing about politics. It was a community hub. It was a "Third Place"—not home, not work, but somewhere in between where you belonged.

Howard rushed back to Seattle, his heart pounding. He told the owners of Starbucks: "We have to do this! We shouldn't just sell beans. We should sell the experience. We should serve espresso!"

The owners looked at him and said: "No."

They told him Americans didn't want espresso. They told him the "restaurant business" was dirty. They refused to change.

Howard was crushed. But he couldn't let the vision go. So, he did the unthinkable: He quit.

Part 3: 217 Ways to Say "No"

Howard decided to start his own coffee company, Il Giornale. He needed $1.6 million to open his first stores.

He had no money. His wife was pregnant with their first child. He had to go hat-in-hand to investors, asking for cash for a coffee shop in a country that drank instant Folgers crystals.

The rejection was brutal.

Howard Schultz pitched his idea to 242 investors.

217 of them said "No."

Some laughed. Some told him coffee was a commodity. Some told him he was crazy to compete with Dunkin' Donuts.

"It was very disheartening," Howard later admitted. "I spoke to so many people who didn't believe in the dream. You start to question your own sanity."

He cried. He doubted. But he kept thinking about the feeling in Milan. And he kept thinking about his father—the man who never had a chance. He couldn't give up.

Finally, he scraped together enough money to open his shops. They were a hit. Two years later, the original owners of Starbucks decided to sell their retail unit. Howard bought them out.

He was now the CEO of Starbucks.

Part 4: The Ghost of Fred Schultz

Now that he was in charge, Howard could finally fulfill the vow he made as a 7-year-old boy.

In the late 80s, retail workers were treated like disposable parts. High turnover. Low pay. No benefits.

Howard stood before his board of directors and proposed something radical: Comprehensive health insurance for all employees. Not just executives. Not just full-time managers. Everyone—even the part-time baristas working 20 hours a week.

The shareholders were furious. "This will kill our profits!" they screamed. "You are giving away money!"

Howard refused to back down. He remembered his father's broken leg. He remembered the debt collectors.

He pushed the policy through. Starbucks became the first American company to offer stock options (Bean Stock) and full healthcare to part-time workers.

When Howard’s father, Fred, eventually passed away, he died a bitter man who felt the world had crushed him. But at the funeral, Howard knew he had honored him.

Part 5: The Crisis of Soul

Years later, in 2008 (the same year Airbnb was struggling), Starbucks was failing. The stock had crashed. The coffee quality had dipped. The "spirit" was gone.

Howard, who had stepped down as CEO, returned to save the company.

He did something no other CEO would do. On a Tuesday afternoon in February, he closed every single Starbucks store in America. 7,100 stores.

He put a sign on the door: "We are taking time to perfect our espresso."

It cost the company $6 million in lost sales for that one day. Wall Street mocked him. The media called it a suicide mission.

But Howard didn't care about the money. He cared about the smell. He realized baristas were reheating milk, killing the romance. He retrained 135,000 employees that day on how to pour the perfect shot with love.

He wasn't saving a balance sheet. He was saving the soul of the company.

The Takeaway

Today, Starbucks has over 35,000 stores.

But the real legacy isn't the Pumpkin Spice Latte. It’s the thousands of employees who could afford chemotherapy, therapy, and surgery because the CEO never forgot what it felt like to be a poor kid in Brooklyn.

Howard Schultz didn't build a business to get rich. He built the company his father never got to work for.

For the Founder reading this:

Your pain is your fuel.

The things that hurt you the most in your past are often the blueprints for what you need to build in the future. Don't run from your trauma—build a solution for it.

Share this article